What is the chronic stage of rheumatoid arthritis?

This stage is usually described as two or more years after initial diagnosis. Clinical practice guidelines usually refer to management in the first two years and beyond two years. Given some people are diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in childhood (usually termed juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) or juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA)), the chronic stage may begin in childhood.

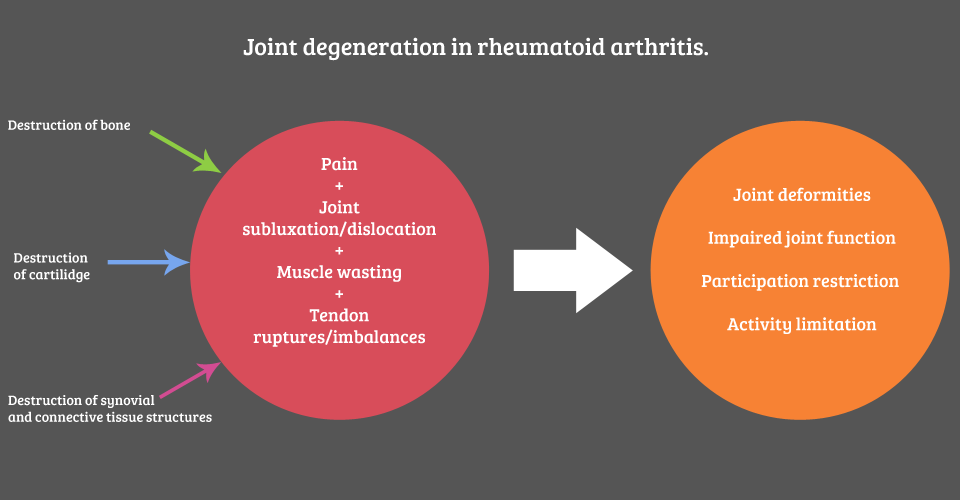

Systemic inflammation continues, causing further articular, peri-articular and extra-articular manifestations. The systemic inflammation leads to destruction of bone, cartilage, and synovial and connective tissues (see Figure 1 below). Vasculitis causes body system and organ-specific complications.

Figure 1: Joint degeneration in rheumatoid arthritis

The video below demonstrates how RA can lead to joint deformity and more.

What are the main issues to be aware of?

- There is a range of clinical presentations during the chronic stage. With appropriate medical management a person may present in remission, with little disease activity and disability.

- Individuals are more likely to experience adverse effects in key body systems (musculoskeletal, neurological, pulmonary, cardiac) if they do not have appropriate medical and pharmacological management.

- The issues raised in Module 2 are still relevant to the chronic stage.

- Individuals’ needs, wants and priorities change over time, and as their experience with the disease develops. Assessment and treatment need to be adapted accordingly. Management of RA is more than just disease control.

- Expect periodic flares in symptoms.

- RA has implications for pregnancy, breast feeding and early parenting:

- The body's immune system changes during pregnancy to accommodate the foetus. For some individuals with RA this is associated with a transient remission of disease symptoms, while others (up to 20%) experience a worsening of joint symptoms and fatigue. These symptoms may become particularly acute post-partum.

- Persons with RA have an increased risk of pre-eclampsia, caesarean section and premature or low birth weight neonates.

- Conception, pregnancy and breast feeding have implications for drug therapy regimens in females and males, which may also impact on symptoms and a person’s emotional wellbeing. Further information about drug therapy issues is available from the ARA website.

- Persons planning pregnancy or discontinuing medications during pregnancy and breast feeding should consult their rheumatologist early.

- The person and their healthcare team should work together to develop a management plan for pregnancy planning, pregnancy and the peri-natal period. Briggs et al describe a practical approach to managing care in this important life stage.

- There are contraindications to treatment and red flags associated with RA.

Practice point: pregnancy with rheumatoid arthritis

In practice this means the physiotherapist needs to educate the person regarding advice and strategies for the impending increase in work/demands associated with motherhood. Helpful information for patients is available from the Arthritis Australia website.

Practical considerations for the physiotherapist working with a pregnant woman and her family, include:

- Educating on ways to lift and carry a baby, to reduce stress on joints.

- Recommending alternative holding positions for breastfeeding/bottle-feeding a baby.

- Providing aids/devices/supports to assist with day-to-day tasks such as changing nappies, getting a baby in and out of a car seat or cot.

- Educating on practical suggestions e.g. buying clothes with zips or Velcro rather than press studs.

This video may be a helpful resource for pregnant women and their families. It is also important to provide information about other sources of support or assistance, for example:

- Local state/territory Arthritis Foundations

- Online support groups (e.g. see Young Women's Arthritis Support Group website)

- Access to home help services

What is your role as a physiotherapist during this stage?

Physiotherapists have long-term involvement in managing persons with RA and are often one of "the constants" in their life.

The physiotherapist’s role is to is to continue to co-manage the person with RA - in partnership with the person with RA, and the other members of the person’s healthcare team. As the disease progresses, clinical features may change or develop. The individual’s needs, wants and priorities will also change over time, and as their experience with the disease develops.

It is important to monitor, and be prepared to respond to changes in:

- Baseline findings (see Module 1). This will include the changing priorities of the person as their experience with the disease develops.

- Articular and peri-articular manifestations (see Module 1).

- Extra-articular manifestations (see Module 4).

Practice point

Assessment and management must continue to take into account the relevant biological, psychological and social factors affecting the person’s function and quality of life. The assessment and management principles outlined in Module 2 remain relevant.

In the chronic stage of RA, team-based care (e.g. GP, occupational therapist, podiatrist, social worker, clinical psychologist) and advocacy become increasingly important.

Below is a video that discusses the role of a physiotherapist during the chronic stage of RA.

Physiotherapists should encourage individuals to comply with medication regimes and monitoring schedules. For example, complying with blood tests and seeking help from their rheumatologist if side effects become apparent.

Important!

Monitor cardiovascular responses to exercise carefully (e.g. unexpected dyspnoea, chest pain)

Are there any safety issues to be alert to and how do you approach them?

Yes, there is a wide range of safety issues you need to consider during the chronic stage of RA. To approach these safety issues, you should:

- Look

- Listen

- Refer

Safety issues to be alert to, including red flags:

Joint instability:

- Pathologic processes associated with RA may lead to joint instability.

- Recognising joint instability in the upper cervical spine is critical (see radiology images below). Instability can lead to sudden, unexpected death or quadriplegia.

- Cervical instability can be asymptomatic, so clinical vigilance is critical, especially when using manual therapy techniques.

- Education about cervical instability is also a duty of care. For example, people with RA with suspected cervical instability should be educated about risks of manipulation and also functional tasks, such as getting hair washed at a hairdresser.

- Refer to Slater et al. for an overview of practical assessment and management strategies for cervical instability.

Vasculitis-driven dysfunction in other body systems:

- Changes in visual, neurological and cardiopulmonary conditions should be immediately referred to a medical practitioner (see Module 4).

Treatment-mediated conditions:

- Bone fragility due to secondary osteoporosis requires considered management approaches and planning (see Module 4).

Disease flares:

- Result in exacerbation of symptoms (pain, inflammation, fatigue, malaise, impaired function) which require:

- Responsive and timely physiotherapy to ameliorate acute symptoms.

- Communication with other care team members including updating interdisciplinary team care plans during/following a disease flare.

Summary

- There is a range of clinical presentations during the chronic stage.

- With appropriate medical management a person may present in remission, with little disease activity and disability. Without appropriate medical and pharmacological management, people are more likely to experience substantial disability and increased mortality.

- Physiotherapists have long-term involvement in managing persons with RA.

- Assessment and treatment need to be adapted over time, taking into account changing needs, wants and priorities.

- There are important treatment contraindications and safety issues relevant to physiotherapy practice.

- Communication and timely on-referral to other care team members is critical - know who these people are and how to contact them.